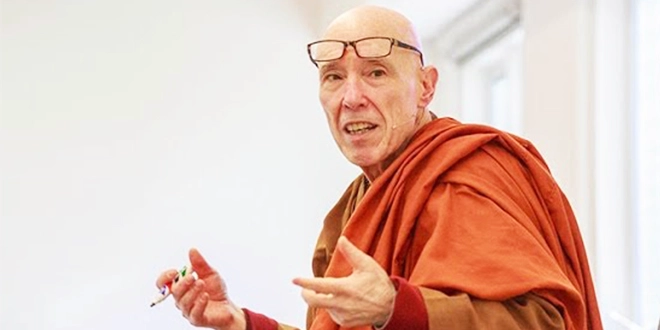

Q&A with Bhikkhu Bodhi on March 7, 2017 at Dharma Realm Buddhist University

Chinese Translated by Ling Chinben & Ma Chinxi

菩提比丘2017年3月7日於法界佛教大學問答紀錄

凌親本、馬親喜 中譯 VBS 590 VBS591

Editor’s Note: On March 7, 2017, Dharma Realm Buddhist University’s Co-curricular Events and Spiritual Life Offices invited Venerable Bhikku Bodhi to host a discussion with the DRBU community. Venerable Bhikku Bodhi is an American Buddhist monk, originally from New York City, who ordained as a monk in Sri Lanka in 1973. He is an eminent scholar and translator of Buddhist texts from Pali into English. His book In the Buddha’s Words: An Anthology of Discourses from the Pali Canon is read and studied in both the B.A. and M.A. programs of DRBU. He is the president of the Buddhist Publication Society and the founder of Buddhist Global Relief, which holds “Walk to Feed the Hungry” in cities throughout the United States; BGR supports projects designed to provide direct food relief to people afflicted by hunger, promote sustainable agriculture, supports the education of women and girls, and gives women opportunities to start right livelihood projects to support their families.

編按:2017年3月7日,法界佛教大學「活動與精神生活共同課程辦公室」邀請菩提比丘為法界佛教大學師生主持一場討論會。菩提比丘是美國籍法師,出生於紐約市,1973年在斯里蘭卡受具足戒。他是知名的學者及譯者,將巴利文經典譯成英文。法界佛教大學學士與碩士課程都研讀他的書《佛如是說:巴利文論藏選集》。他是佛教出版協會會長,並創立「佛教全球救濟會」在全美各城市舉辦「為飢餓健行」活動,募款所得用以支持直接將食物送給挨餓者項目、提倡永續農業、支持女性與女孩受教育、提供正當機會給女性工作創業,以支持她們的家庭。

Bhikkhu Bodhi: In my early days as a monk, I focused my study primarily on the scriptural languages of Pali and the discourses of Buddhist scriptures. Most of my effort was invested in translating Buddhists text from Pali into English. In recent years, there has been a shift in my points of emphasis, particularly when I came back to the United States in 2002. I began to get more information about world events and I began to see the need to develop what we might call a Buddhist conscience in the great challenges that are facing humanity today; particularly we see challenges on several fronts. One challenge is widening income inequality. The country’s and world’s wealth are channeled into the hands of a very small, powerful, and ultra-wealthy elite to the detriment of millions of people around the world who are being plunged into unconscionable poverty and misery.

菩提比丘:出家初期,我的研究重點是巴利文經文語言和佛經論述,我的大部分精力都用於將佛經從巴利文翻譯成英文。近年來,我的研究重點有所改變,特別是2002年回到美國後,我常聞各種天下大事,並開始意識到,在人類面臨的巨大挑戰面前,當今社會需要發展所謂的「佛化良知」。人類面臨如下挑戰:一是貧富不均日益加劇,這個國家乃至整個世界的財富都集中到極少數權貴精英手中,致使世界上千千萬萬窮人陷入極度貧困和痛苦之中。

Another challenge is the development of weapon systems and militarization. We invest more and more of the country’s wealth into the military to build up this country. The extension of the American empire project into the Middle East, igniting wars there, costs hundreds and thousands of innocent lives. And probably the most ominous trend of all is the continued exploration and exploitation of fossil fuels. Burning up carbon and expelling it into the atmosphere causes climate changes that will precipitate mass disasters around the world. The particular question and problem I’m been dealing with is “How do we develop a Buddhist response to these problems, based upon the intrinsic values of Buddhism, as a doctrinal framework of Buddhism?” I’ve noticed there’s always a tendency of Buddhists, particularly Buddhist monastics, to shy away from facing these problems and deal with them head on, as though this is part of the dirty world we have to avoid in our efforts of purification. Everything is interconnected; in the Buddhist doctrine, this means the development of our own inner spirituality has to be reflected in the way we respond to that in the world. If our inner spiritual cultivation has any value, it has to be applied in compassionate action to protect those people who are most vulnerable around the world and to preserve a viable, healthy human community, which will help people to flourish rather than to flounder at the very edge of survival.

另一是武器系統和軍事化發展迅猛,這個國家把越來越多的錢用以裝備軍隊,把帝國項目擴展到中東,引發戰爭,使成千上萬的無辜平民死於非命。可能最糟糕的趨勢還是繼續勘探和開採化石燃料。碳燃燒、碳排放所致的氣候變化將在全球引發嚴重災難。我一直在思考和處理的問題就是,「根據佛教教義所闡述的佛教內在價值觀,我們作為佛教徒,應該如何對這些問題作出應答?」我注意到佛教徒、特別是佛教僧侶們都有一種傾向,不願直接面對這些問題,對此避而遠之,彷彿這些便是我們在清淨修行中必須避開的五濁惡世的組成部分。然而一切都是相互關聯的,在佛教教義中,這意味著我們內在靈性的發展必須反映在我們對世界的反應中。如果說我們內心修養要具有任何價值的話,那必須是慈悲為懷並行動起來,去保護世界上最弱勢的群體,保護切實可行的健康的人類社區,從而幫助那裡的人們蓬勃發展,而不是在生存邊緣垂死掙扎。

Question: In reading your book in our Pali text class, it seems like a Buddhist attitude to find a secluded place and to move through these stages of cultivation. But with your call to action, how do you find a balance between those two things such that we can actually engage effectively but also continue to do so from a place of stability?

問題:我在巴利文經典課上閱讀您的書後,覺得佛教徒看上去是需要找一個寂靜處,然後次第循序漸進地修行。但您又呼籲佛教徒需要在世上行動起來,您是如何找到這兩者的平衡點?既能積極有效地行動起來,又可繼續安穩地修行?

Bhikkhu Bodhi: I would say this is something each person has to work out for themselves, how to strike a satisfactory balance between inner cultivation and outer action, or action in the world. This balance will differ for each individual. But what I would say as a generalization is for action in the world to be truly transformative and effective, it should come from a place (to some degree) from inner stillness, stability, and balance, and also as an expression of true compassionate concern for others and for the wellbeing of the world; and not come from the position of anger, aggression, hostility toward those with whom one disagrees. This will bring together the two pillars of Buddhism, the classical pillars of wisdom, which is to investigate and understand at a deeper level the causal origins of problems and to see the underlying causes and conditions. When we engage in cultivation, we then see all of the problems that we face in our personal lives are really coming from the afflictions or the defilements of the mind. From this, we can understand that the societal and global problems of the world all come from the collective merger of the defilements of millions and billions of human beings. One has to be able to go down to the deepest level of the underlying sources of the defilements and then begin to work on ourselves. I would also say that in today’s world, we’re all so closely interconnected that it’s not sufficient just to go off full-time by oneself to cultivate inner insight and purification. But as we develop through different stages of inner insight and purification, we should contribute our realizations and skills to transforming the nature of society and work to bring about a more equitable world.

菩提比丘:要說這是每個人必須自行解決的問題,即怎麼在內心修行和外在行動(在世上的行動)之間找到一個令人滿意的平衡點。這種平衡因人而異。不過總而言之,如果希望在世上的行動真正能夠改變世界並且卓有成效的話,它應該(在某種程度上)出自內心的平靜、穩定和平衡,表達對他人和世界福祉的慈悲關懷,而不是來自對不同觀點者的憤怒、攻擊和敵意的立場。這就把佛教智慧的兩大支柱結合起來,即深入地調查和理解問題的緣起,並且看到其根本的因緣。當我們修行時,就會發現,我們在個人生活中面對的所有問題,都來自內心的煩惱和污染。由此我們可以理解社會問題和全球問題都來自於億萬眾生內心污染所致的共業。一個人必須深入到最深層的根本污染源,並且從自己的改變做起。在當今世界,我們大家是如此的休戚與共,因此我們僅僅去修行個人的智慧和清淨是遠遠不夠的。當我們通過修行智慧和清淨達到不同的位次之後,我們應該為改變社會性質、開創一個更為公平的世界貢獻自己的智慧和技能。

Question: I was just wondering, what is your advice or thoughts on navigating some of the relationships we have with the people in the world that may share different kinds of ideas, orders, or faiths?

問題:在與不同理念、不同信仰、不同宗教團體的人們互動方面,您有何建議和想法?

Bhikkhu Bodhi: I would say that we shouldn’t try to impose our views on those who do not seem like they will be receptive to us. If people are already fixed in their own beliefs, commitments, and worldview, then we just relate to them at a level where we have some kind of common interest; but we shouldn’t try to convince them or impose our beliefs upon them. Just as we or I wouldn’t want a person from another faith came in and tried to impose their beliefs on me. I would sort of back off and resist. So we could suppose other people would resist our attempts to impose our views on them.We can try to find areas of common understanding but when we run up against differences, we just have to recognize them and respect the differences. I remember a line that was maybe in an earlier translation of the Sixth Patriarch Sutra, where Master Huineng says, “When you meet those whom disagree with us, we just put our palms together and keep silent.” I think it is something like that.

菩提比丘:我們不應該試圖把我們的觀點強加於看起來不會接受我們觀點的人。如果他們已經有了固定的信仰、承諾和世界觀,那我們只需在與他們有共同興趣的層面上進行溝通,而不要試圖去說服他們,或把我們的信仰強加於他們。就像我們也不想讓別的信仰的人來把他們的宗教強加於我們頭上一樣。對此我會停止交流並予以抵制。所以我們可以設身處地想想,如果我們把自己的觀點強加於他人,勢必也會引發他們的抵制。我們應當努力發現與他們有相同見解的領域,但如果遇到分歧時,我們則必須認識清楚,並尊重這些分歧。我記得可能是《六祖壇經》早期譯本中的一句話,惠能大師說,「若言下相應,即共論佛義,若實不相應,合掌令歡喜。」我想就是這個意思。

Question: Would you please kindly share some of your observations on trends of how you see Buddhism developing or evolving in this country, and perhaps some of the things that are encouraging or lacking in areas?

問題:請分享您關於佛教在這個國家發展和演變的觀察及趨勢,比如哪些地方令人鼓舞,哪些有待改進?

Bhikkhu Bodhi: One major development that’s taking place in American Buddhism, I say with a little sadness, is almost a shifting of the responsibility of bearing the torch of the Dharma from the monastic community to the lay people, to lay teachers. On one hand, I think it’s good that more and more lay people become involved in Buddhist practice and delve deeper in Buddhist studies. Along this, however, there’s also the trend that once more lay people get involved, they almost autonomously start developing approaches to the Dharma on their own, resulting in more compromises in the flavor, or even a dilution of the flavor, of the Dharma from making the Dharma more palatable to people living in the world.

菩提比丘:不無悲哀地說,美國佛教的一個重大轉折是,佛法火炬手的精神和責任從出家人轉移到了在家人、在家老師的身上。一方面,我認為越來越多的在家人參與到佛教修行和佛教研究是件好事。但在這個過程中,還會產生一種趨勢,一旦更多的在家人參與進來,他們幾乎都會不由自主地按照自己的方式修法,從而導致佛法有更多的妥協,使原汁原味的佛法被稀釋,以便佛法更加適合世界上的世俗大眾。

For instance, when one wants to sell something like a popular healthcare brand, or an alternative lifestyles fund, everyone immediately becomes interested if you just attach the word “mindfulness” to the product. This has been a tendency that’s been happening. I would say there’s a real need to have stronger monastic presence in American Buddhism. With this, I feel monastics also need to recognize the need to make the Dharma more relevant to people living in the world without compromising the essential foundations of the Buddhadhamma in order to popularize the religion. Some important things drop out in people’s attempt to popularize Buddhism. For instance, some monks have told me that they almost never mention karma and rebirth and other realms of existence or hear about these in the popular discourses on Dharma. For me, I come from a Sri Lankan background where these notions are always mentioned in the background of the teaching, so I never have any hesitation about speaking about kamma and reincarnation. I think to preserve the integrity of the Buddhadhamma one does have to recognize that there are other realms of existence, that there is a process of rebirth where we go from one life to another, migrating through these different realms of existence, and that there is a fundamental, ethical law which connects the existences in one realm to another, that is the law of kamma and its root.

例如,當某人想在流行的醫保品牌下或者另類生活基金中出售一些東西時,如果在產品上標上「正念」一詞,立即會引起每個人的興趣。這種趨勢正在發生。我想強調美國佛教界真正需要更為強大的僧團存在。在此基礎上,為了普及佛教,我認為僧侶們需要意識到,在不損害佛法基本原則的基礎上,要努力把佛教與這個世上的人們更多地聯繫起來。在人們普及佛教的過程中,一些重要的東西被放棄了。例如,一些僧侶告訴我,他們幾乎隻字未提「業力」、「輪迴」和其他法界的存在,或者在佛法的通俗演講中也未聽過這些內容。對於我而言,我有斯里蘭卡修行背景,在這個教育背景下經常會提到這些,因此我從來就是毫不諱言地談論「業力」和「輪迴」。我認為要維護佛法的完整性,必須認識到其他法界的存在,即存在從這一世遷徙到另一世的不同法界間的輪迴過程,存在維繫此法界與他法界的基本倫理法則,也就是業和因果報應法則。

Question: Right now in our class we’re looking at all of the stages of spiritual development. After one overcomes the hindrance and jhanas there’s a part about remembering your past lives; how do we know that really happens for a practitioner or is it pointing to some kind of practice or thing we should be cultivating in our own lives presently?

問題:我們班上正在探討靈修的每一個階段。當一個人克服了障礙並入禪定後,有一部分內容是對前世的回憶;我們怎麼知道對於一個修行者來說這些真的發生過,或者只是它指出了某種修行或我們此生應該修行的事情?

Bhikkhu Bodhi: I think certainly in the framework of understanding of the texts themselves, it does mean literally recollecting one’s previous lives. This is not something that is considered obligatory or feasible for everybody. This is from the sutras from Majjhima Nikaya where we find the full presentation of the past involves the development of the four jhanas, meditation absorptions. Based on the fourth jhana comes the surreal higher knowledge and recollection of past lives, the divine eye, which allows one to see pass the rebirth of others and gain knowledge of the destruction of the defilements. For those who develop and really master the four jhanas, they gain a very strong degree of samadhi concentration and great clarity of mind and be able to send the mind back over the events of this present life, even to the point of one’s biological birth and to the conception in the womb. By persisting in that attempt at recollection, one could break through that barrier that separates one’s conception in this life and one’s previous life, and then break the mind immediately preceding this life. Through systematic development, one could acquire the ability to recollect more and more past lives. Maybe at a more accessible and practical level, one could do meditative reflections on the fact that we each have lived many past lives in different realms of existence for present condition and our future.

菩提比丘:我認為從經文字面上看,確實含有回憶個人前世的內容,但對於每個人來說不都是必須的或可行的。《中阿含經》中有通過四禪、入定而看到過去生的完整描述。在第四禪的基礎上獲得超現實的更高知識和對前世的回憶,天眼打開,能看到他人的過去生,並獲得消除染污的能力。對於那些開發並真正掌握了四禪的人來說,他們能深深入定、心甚明了,就能把心送回到此生的各個事件中,甚至到出生時,乃至在母親子宮受孕的時候。通過堅持嘗試這種回憶,有人就可以打破分割前世和今生受孕之間的壁壘,從而看到前生的記憶。經過系統訓練,此人能回憶起越來越多的前世。或者從對大家更容易做到和更實用的角度看,我們可以打坐冥想這個事實:我們每個人已經在六道裡面經歷了許多世,直到今生今世,並且還將繼續下去。

Question: We’re hoping you could talk about the concept of nirvana and how that relates to bodhi and the image of a candle being snuffed out.

問題:我們希望您談談涅槃的概念和菩提與蠟燭息滅圖像之間有怎樣的關聯。

Bhikkhu Bodhi: There are three aspects to nirvana. I take nirvana to be an unconditioned dharma, an unconditioned state and reality describe in some sutras as that which is not born or unconditioned, and which does not become or change. Elsewhere it is called the birthless, the ageless, the deathless, the undefiled, and the unconditioned. That is nirvana in itself. Then there are two stages in the attainment of nirvana, which are called the nirvana element with residue and the nirvana element without residue. These two stages in the attainment of nirvana are distinguished most explicitly in a very short sutra in the collection called the Itivuttaka, it could be sutra number 42 or 44, a minor book of the Pali cannon. The nirvana element with residue is the extinction of greed, hatred and delusion attained by an Arhat liberated while alive; the nirvana element without residue is that which is attained when the Arhat passes away. That sutra describes nirvana as attainment without residue where the breakup of the body and the extinguishing of life force becomes cool right there. Some interpreters of the one Theravada camp say that nirvana is only the extinction of defilements in this life and ending the process of birth and death; the other school of interpretation says it’s not sufficient to base one’s understanding of nirvana just on the two awakening elements, and that we have to also bring in description of nirvana as being the unborn, unbecome, and unconditioned. I see that these are two stages in the attainment of unconditioned. One is the passing away of the Arhat likened to a flame that goes out; it’s sometimes used as a simile in the Ratana Sutta—Nibbanti dhîrâ yathâ’ ya ṃ padîpô as an extinguishing flame. And nirvana from the angle of conditioned existence is conditioned existence that goes out, but there’s still the unconditioned. We could even say the attainment of nirvana without residue is the act by which the liberated one passes from conditioned existence into the unconditioned.

菩提比丘:涅槃有三個方面。涅槃是無為法、無為的狀態和實相,正如一些佛經中所描述的那樣:它不生不滅和無為不變。有的地方稱為無生、無老、無滅、無染污和無為,這是指涅槃本身。在證得涅槃的過程中有兩個階段,分別稱為有餘涅槃和無餘涅槃。達到涅槃的這兩個階段在《如是語經》的極短經文中表述得最清晰,它可能在巴利大藏經中的一小本里(第42或44號經文)。有餘涅槃是熄滅貪嗔癡的阿羅漢在生前獲得的;無餘涅槃是指阿羅漢死後獲得的。經文中這樣描述無餘涅槃:肉體煙消雲散,生命之火熄滅。一個南傳學派的解釋是,涅槃僅僅是指此生染污除滅,生死已斷。另一宗則說,基於有餘、無餘兩個覺醒元素來理解涅槃是不夠的,我們必須也要把涅槃描述為無生、無起和無為。我認為證無為有兩個階段,一個是阿羅漢死亡,猶如火焰熄滅;在《三寶經》中有時用火焰熄滅來比喻涅槃。從有為法的角度來說涅槃,即便有為法滅了,但無為法依然存在。我們甚至可以說證得無餘涅槃正是解脫者從有為法入無為法的行為。

Question: I was able to go to your talk on Saturday and I heard you talk a lot about faith. I wondered if you could touch on that a little bit here. What exactly is faith? And what or where do you put this confidence in? I would also appreciate it if you could share a little bit about your personal journey.

問題:我周六去聽了您的演講,聽到您講了許多關於信心的內容。我想您能否就以下問題略談一二:究竟什麼是信心?您把信心放在何處?如果您能分享一下您的人生經歷,我將不勝感激。

Bhikkhu Bodhi: In my talk that I gave at Abhayagiri Temple on Saturday was based on a short sutra in the Samyutta Nikaya. There are two verses of riddles that are addressed to the Buddha by a yaksha, a demonic being. The first riddle in each verse asked about faith. In the first verse, the yaksha asked what is the best treasure for a person? The Buddha responds, “Faith is the best treasure for a person here.” In the second verse, the demon asks how does one cross the flood and the Buddha answers, “With faith one crosses the flood.” What I explained on Saturday is that the two pairs of verses are concerned with different aspects of the Buddhadhamma. The first pair of verse is concerned with what I might call mundane or world applicable aspects of the Buddha’s teaching. This is an aspect Buddhism that is shared with other spiritual traditions of ancient India. It’s based on recognition of a moral law that is fundamental to the nature of the universe—the law of kamma. This is the recognition that there are actions in accordance with and actions that violate the moral law. It is our responsibility to seek our true well-being and happiness to act in accordance with that moral law. In the first verse, I understand faith in the reality of this moral law. It is faith in the wisdom of the spiritual teachers who teach the moral law, and faith that acting in accordance with this moral law is to benefit oneself and others in the world. This is a thing that is not unique and exclusive to the Buddhist teaching. It’s a faith in the spiritual realities or spiritual principles that underlie the unfolding of events in the world.

菩提比丘:我周六在無畏寺的演講是根據《相應部》中的一段簡短經文。有個夜叉給佛陀說了兩個偈頌難題。每個偈頌裡的第一個難題都是關於信心的。在第一個偈頌裡夜叉問,對於人來說,最寶貴的財富是什麼?佛陀回答,「對於這裡的人來說,最寶貴的財富是信心。」在第二個偈頌裡,夜叉問一個人如何穿越洪水,佛陀回答,「用信心穿越洪水。」我在周六解釋說,這兩個偈頌涉及佛法的不同方面。第一個偈頌涉及佛教教義在世俗世界的應用。這一點是佛教與其他古印度精神傳統都認同的。它基於下面這個認知:宇宙之本的道德法則就是業力法則。這是認識到既有符合道德法則的行為,也有違背道德法則的行為。我們有責任按照道德法則行事來謀求我們真正的福祉和幸福。在第一個偈頌裡,我以此道德法則為真實不虛來理解信心,這是對精神導師的智慧而產生的信心,他們的一舉一動都依此道德法則,造福自己和世人,並以此開展道德法則和信心的教育。這不是佛教教育獨有的,這是對世事發展之本質的精神現實或精神原則的信心。

On the other hand, faith in the second verse in the line by “faced with crossing the flood,” which I understood to be the special faith in the Buddhist teaching as the means to cross the flood. The flood is a metaphor for samsara, the cycle of birth and death or the flood of defilements in the mind. In this case, it is placing faith in the Buddha, as the fully enlightened one and in his teaching, the Dhamma, as the path to liberation so one is able to cross the flood of samsara and reach security, the other shore of nirvana.

另一方面,第二個偈頌裡「面臨穿越洪水」的信心,我理解這是佛教教育中借喻穿越洪水的特殊信心。洪水隱喻輪回、生與死的迴圈,或指內心染汙之洪水。在這種情況下,相信大徹大悟的佛陀,他的教導,也就是佛法,即是説明人們穿越輪回洪水、到達安樂的涅槃彼岸的解脫之路。

That is the distinction I make in the two aspects of faith. Personally, when I first came across Buddhism, I don’t recall I was ever really struggling with the teaching of kamma and rebirth. One of the first writers on Buddhism that I read was Alan Watts. At that time he popularized the thought of D. T. Suzuki, but he didn’t really write very much about rebirth or kamma at all. To the extent he mentioned it, he gave a rationalized explanation of it as just a metaphor describing how people undergo different states of mind. I at first took his words to be authoritative until I started to read Buddhist texts for myself. I saw the texts were quite clear and explicit about the reality of other realms of existence and about the fact of rebirth. I didn’t go through any struggle, I thought this is coming from the Buddha and so it must be true. It made sense to me and I’ve developed what I take to be rational arguments in favor of the teaching of kamma and rebirth. When I come across skeptics, I use a more modern analogy for them to understand. When I see people sitting in the audience with their iPads or iPhones, perhaps collecting messages from friends from France, Italy, Taiwan, or Japan. You get these messages coming on your wireless iPad or iPhones. I ask them, “How are you getting your messages?” And they tell me they just get them from Taiwan, Italy, and France. That’s just your Western cultural baggage. If you reflect, the analogy is quite close, things you can’t see, can’t touch, and can’t verify outside the range of sensory perception. If that can be the case with electronic devices, it can also be the same with consciousness. Consciousness is an energy, which gets attracted to the appropriate receptor.

這以上就是我說的信心在這兩個方面的區別。就我個人而言,開始接觸佛教時,我不記得我在接受業力和輪回的教導中有任何問題。我讀的第一本佛教書的作者是艾倫‧瓦茲。那時候他傳播了鈴木‧大拙‧貞太郎的思想,不過,關於輪回和業力方面,他確實沒有寫很多。在他提到的範圍內,通過描述人們怎樣經歷不同心理狀態的比喻,來合理化他的解釋。起初,我把他的話當作權威,直到我開始親自閱讀佛教經典。我在經文中讀到,其他法界真實無虛地存在,輪回的事實也講得清晰而明確。我沒有經歷任何思想鬥爭,我想這是佛陀所說,所以必定真實無疑。這對我而言很有道理,我發現了支援業力和輪回教法的合理論據。當我遇到懷疑論者時,我會用更為現代的比喻來讓其理解。當我看到人們拿著iPads或iPhones坐在觀眾席上時,他們或許在接收來自法國、義大利、臺灣或日本朋友的資訊,這些資訊被 iPads或iPhones接收到。我問他們,「你們是怎樣收到資訊的?」他們告訴我,他們從臺灣、義大利和法國接收到的。這恰恰是你的西方文化包袱。如果你反思一下,這個比喻是非常貼切的,你不能看見它們,不能觸摸它們,也不能在感官感知的範圍之外加以驗證。 如果說電子設備是這種情況,那麼識未嘗不是如此。識是一種能量,它可以被適當的接收器接收到。♦